In the earliest known work of literary fiction, The Epic of Gilgamesh (2700 BC), jeweled trees figure. The hero’s journey begins at a grove of cedars, which are guarded by the monster Humbaba, and ends at the otherworldly trees that bear rare jewels for fruit. These marvellous trees exist in a garden at the end of the tunnel from the sun, which Gilgamesh enters alone. The two types of trees—cedar and jeweled—represent the boundaries of the physical world.

Who can forget one’s first experience with Ovid? Whether it was in the unit on Greek and Roman mythology in Year 5 or the magical Humphries translation of Metamorphoses widely assigned in universities. All those fantastic stories about women (and sometimes men) in flight, calling for help and getting it by way of transformation. Remember Daphne, a young woman with a beautiful face who prefers woodland sports over sporting with men, and Apollo, who is seized with love for her? Quite naturally, a chase ensues. And just as Apollo is about to catch her, she calls out: “Help me, open the earth to enclose me, or change my form, which has brought me into this danger!” With that plea, her skin becomes bark, her hair turns into leaves, her arms are transformed into branches, and her feet grow into the ground. Apollo embraces the branches, but even they shrink from him. Grieving, Apollo calls on his powers of eternal youth to ensure Daphne will never die. This dramatic story is offered as a poetic explanation for why the leaves of the Bay Laurel tree are ever green.

In Paradise Lost, Milton describes the ‘Tree of Life’ in this lush way: “High eminent, blooming Ambrosial Fruit Of vegetable Gold… Flours of all hue…the mantling vine Layes forth her purple Grape, and gently creeps Luxuriant”. Later, he chides Satan for turning himself into a cormorant and using the highest branch of the ‘tree of life’ as a perch from which he might devise the death of others, ignoring the gifts and riches of eternal life.

Sir Walter Scott’s novel Guy Mannering (1815) features a ‘Dule’ tree, which was also known as the ‘justice’ tree, the ‘gallows’ tree, and the tree of ‘lamentation and grief’. Highland Chieftains regularly hanged enemies, traitors and common criminals from Dule trees. Such trees were located on high ground at busy thoroughfares, where the rotting bodies hung for a considerable time as a warning to all who passed by.

Coverdale, the narrator of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s exquisite novel The Blithedale Romance (1852), climbs halfway up a white pine in which a wild grapevine had “twined and twisted itself up into the tree, and after wreathing the entanglement of its tendrils around almost every bough, had caught hold of three or four neighboring trees, and married the whole clump with a perfectly inextricable knot of polygamy.” From this airy chamber, Coverdale composes verse, shirks work, and spies on other members of the commune. (Blithedale is based on Brook Farm, a 19th century utopian experiment in communal living inspired by American transcendentalist writings. Interestingly, major figures like Emerson, Thoreau and Poe questioned the community’s idealism and values. The experiment failed within seven years.)

In the shade of the house, in the sunshine of the riverbank near the boats, in the shade of the Sal-wood forest, in the shade of the fig tree is where Siddhartha grew up, the handsome son of the Brahman, the young falcon, together with his friend Govinda, son of a Brahman. The sun tanned his light shoulders by the banks of the river when bathing, performing the sacred ablutions, the sacred offerings. In the mango grove, shade poured into his black eyes, when playing as a boy, when his mother sang, when the sacred offerings were made, when his father, the scholar, taught him, when the wise men talked. Thus begins Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha, An Indian Tale (1922).

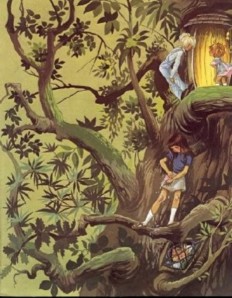

The four books of The Faraway Tree series by Enid Blyton (published between 1939 and 1951) are beloved children’s stories that feature one of the wildest fictional trees of all time. It’s inhabited by a crazy assortment of magical creatures, all with unusual visages, habits and predilections. But the most interesting thing about the tree is that at the top there is a ladder that leads to a magical land. Each time the children visit, the land is different: sometimes awful, like the Land of Dame Slap, ruled by a cruel schoolteacher; sometimes enjoyable, like the Land of Take-What-You-Want.

In 1767, the twelve year old Baron Cosimo Piavosco di Rondo refuses to eat his dinner of snails and in a tantrum takes to the trees, where he lives out the rest of his life. He doesn’t live in only one tree, but in a Europe more heavily forested than today, he travels long distances from tree to tree never placing his feet on the ground. A whimsical novel steeped in history and philosophy, Italo Calvino’s The Baron in the Trees was first published in 1957.

In The Botany of Desire: A Plant’s Eye View of the World (2002), Michael Pollan looks at the social history of the apple tree and reveals the truth behind the Johnny Appleseed legend—it was all to do with moonshine.

One of my favourite recent novels is Eucalyptus (1998) by Murray Bail, which won both the Miles Franklin Award and the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize in 1999. Set up like a fairy tale, Ellen Holland’s unusual beauty causes her father much concern until he devises a contest: the man who can name all the eucalyptus species on his rambling property will win her hand in marriage. Many try, a few come close, and just as it looks as though one will succeed, Ellen’s true love arrives with the crush of eucalyptus leaves under his boots and an inarguable solution.

love this page: i am writing an essay entitled trees with an emphasis on trees within literature and cinema

thank you for sharing your knowledge

[…] •All Literature Ever Made: Jesus christ look at all these trees. Look at them. […]

it strikes me that eucalyptus is not just set up like a fairy tale, but like Ovid’s Metamorphoses themselves, in that it comprises a collection of loosely related myths, some of which involve transformation. From memory, the stories of Diana and Actaeon, Tireisias and several others are adapted and parallelled by Bail.

oooh, you make me want to read it all over again!

[…] •All Literature Ever Made: Jesus christ look at all these trees. Look at them. […]